By Emily Tilby, PhD Student in the Department of Archaeology

Last summer I was lucky enough to take part in a season of excavations at Shanidar Cave in the foothills of the Zagros Mountains in Kurdistan, northeastern Iraq, as part of an ongoing project investigating the chronology, environmental context and hominin use of the Cave and the wider region. I was nervous as this was the first “proper” archaeological dig I had ever attended, only having briefly taken part in a training dig just outside Cambridge previously, but the whole experience was amazing and one of the best parts of my PhD so far.

Shanidar Cave is an iconic site in Palaeolithic archaeology. It was initially excavated in the 1950s by Ralph Solecki and colleagues, and the material recovered from these excavations included the remains of around 10 Neanderthal individuals. The unusual orientation of some of these individuals as well as potential indications of ritual behaviour associated with the hominin remains led Solecki to interpret some of the remains as Neanderthal burials. This particular interpretation, or at least the evidence it is based on, has been questioned by subsequent researchers but the site and its collection of Neanderthal remains continue to feature in debates over Neanderthal burial and social behaviour.

The full sequence of hominin occupation in the cave spans a very long period, potentially extending back as far as 150,000 years ago. This also offers us the opportunity to another key question concerning Neanderthals; when and why did they go extinct? Current evidence from southwest Asia suggests that Neanderthals were extinct in the region by approximately 40,000 years ago and several hypotheses have been put forward to explain this extinction event. One hypothesis is that Neanderthals were less able to cope with abrupt or severe climatic changes which led to their eventual demise both in the region and globally. Whilst global climatic records for this period are available, in order to fully understand Neanderthal responses to climatic and environmental changes it is necessary to have local or regional records from areas that were actually inhabited by hominins, and the stratigraphic sequence from Shanidar Cave offers this. The focus of my research is the microfauna from the new excavations. The definition of microfauna varies, but generally it refers to animals with a live weight of less than 2kg, which in my case mostly means rodents such as voles. Microfauna generally have short generation times, small home ranges and relatively specific ecological niches which makes them excellent high-resolution local environmental records.

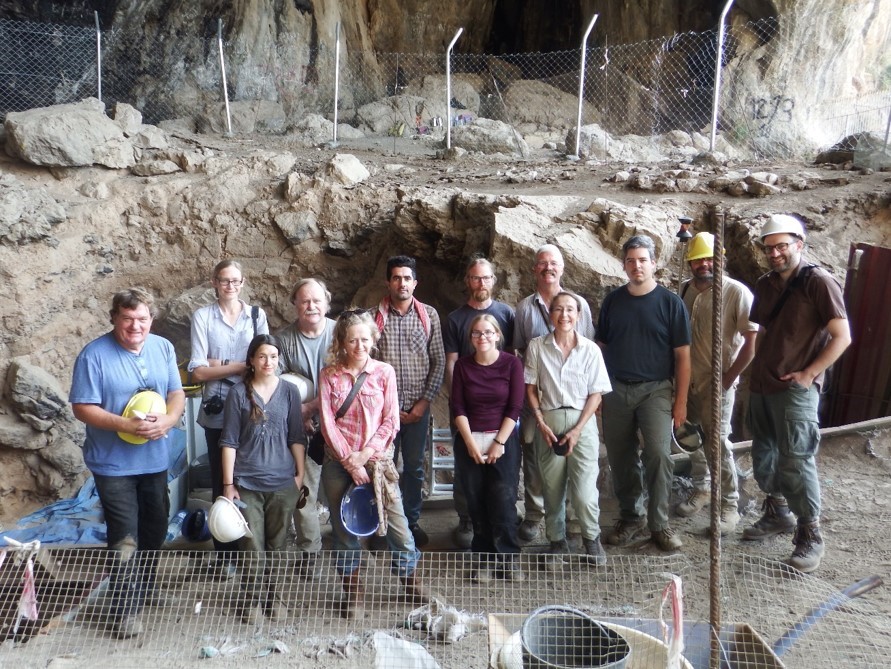

In 2014 an excavation permit was awarded to my co-supervisor Professor Graeme Barker by the Kurdistan General Directorate of Antiquities and excavations began at the site in 2015, followed by further excavation seasons in spring and summer 2015, 2016, spring 2017 and summer 2018. Last year’s fieldwork ran from the end of August to the end of September, with a small initial team heading out for the first week followed by the remainder of the team for the final three weeks of excavations. In all there were a dozen members of the team led by Professor Barker, with representatives from Birkbeck University, Liverpool John Moores University, Queens University Belfast, Cambridge University, the Canterbury Archaeological Trust and the Kurdistan General Directorate of Antiquities. The cave is situated within a wider archaeological reserve including a building kindly made available by the Directorate of Antiquities as the resthouse and work station for the team. One of the hardest parts of fieldwork was dealing with the extreme heat: temperatures could reach 43˚C in the shade, resulting in even the tap water coming out burning hot, and when all materials and equipment have to be carried up and down the 240 steps between the resthouse and the cave this can be quite challenging. We started early in order to make the most of the cooler hours just after dawn, with part of the team heading up to the cave to continue excavations whilst the remainder stayed at the rest house to help wet sieve and sort the excavated material. The aim is to collect all archaeological materials larger than 2 mm. I was mostly involved in the sorting of material as it came down from the cave as this is where the specimens I work with would be sorted out from other materials such as the lithics and shells.

Aside from the excavations, one of the most interesting parts of fieldwork was the landscape and wildlife around the site. The landscape around the cave is very dramatic, especially in the early morning or looking out across the valleys from the area above the cave. Despite the heat the landscape was also incredibly biodiverse; a spring at the back of the cave attracted herds of ibex, owls and various other animals which left their footprints on the dusty floor of the cave. Although we didn’t meet them face to face, we could also hear wolves and hyenas howling across the valley in the evenings. Various scorpions and centipedes were seen around the rest house, with the latter even turning up in someone’s bed (happily without its normal occupant!).

One of the most exciting finds from last year’s excavations were new articulated remains from the upper body of a Neanderthal adult, including the skull, which were conserved and excavated and are being analysed by Dr Emma Pomeroy here in Cambridge. They are the first articulated remains of a Neanderthal found in the last 35 years. Being able to see the remains in-situ was fantastic, and we recently got to hear an update on them in January as members of the project got together with other scientists for a workshop on “Neanderthal Notions of Death and its Aftermath: The Contribution of New Data from Shanidar Cave” funded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. The workshop was an opportunity for the various team members, including myself, to present our current research to date, and also to find out more about what else had been going on in parts of the project.

Overall the fieldwork last year was one of the highlights of my PhD so far. Being able to see exactly where my material comes from really helped me to understand the context of my samples and my work much better. The discovery of the new Neanderthal skull and the discussions at the Shanidar workshop have also helped me to better understand the archaeological significance of the new excavations, as well as reaffirming to me why my project really matters!