By Sam Coffin

PhD Student at the British Antarctic Survey and Department of Plant Sciences.

In January 2019 I started the mammoth 9500+ mile journey to reach the “land of always winter”… Antarctica. What laid ahead was two months of field work collecting diatom specimens for my PhD research. No need to sweat though, as temperatures down in Antarctica during the summer hover around 0°C and that’s before factoring in wind chill. My name is Sam Coffin and I am an algal physiologist at the British Antarctic Survey and Department of Plant Sciences at Cambridge University. For those who do not know what an algal physiologist is, simply put it is someone who studies the biological processes and functions of algae which enable them to live. Currently my research focuses on one particular type of algae called “Diatoms” and specifically those found in the polar regions. Now, for any established diatom lovers you will understand that being able to observe diatoms in Antarctica presents an amazing opportunity to witness diatoms in one of their most dominant environments on Earth. For those of you who are not yet fully familiar with these microscopic gems, I hope this blog post will enlighten you on the beauty and importance of these microscopic organisms and give you an insight to Antarctica.

So what are diatoms and why should we care about them?

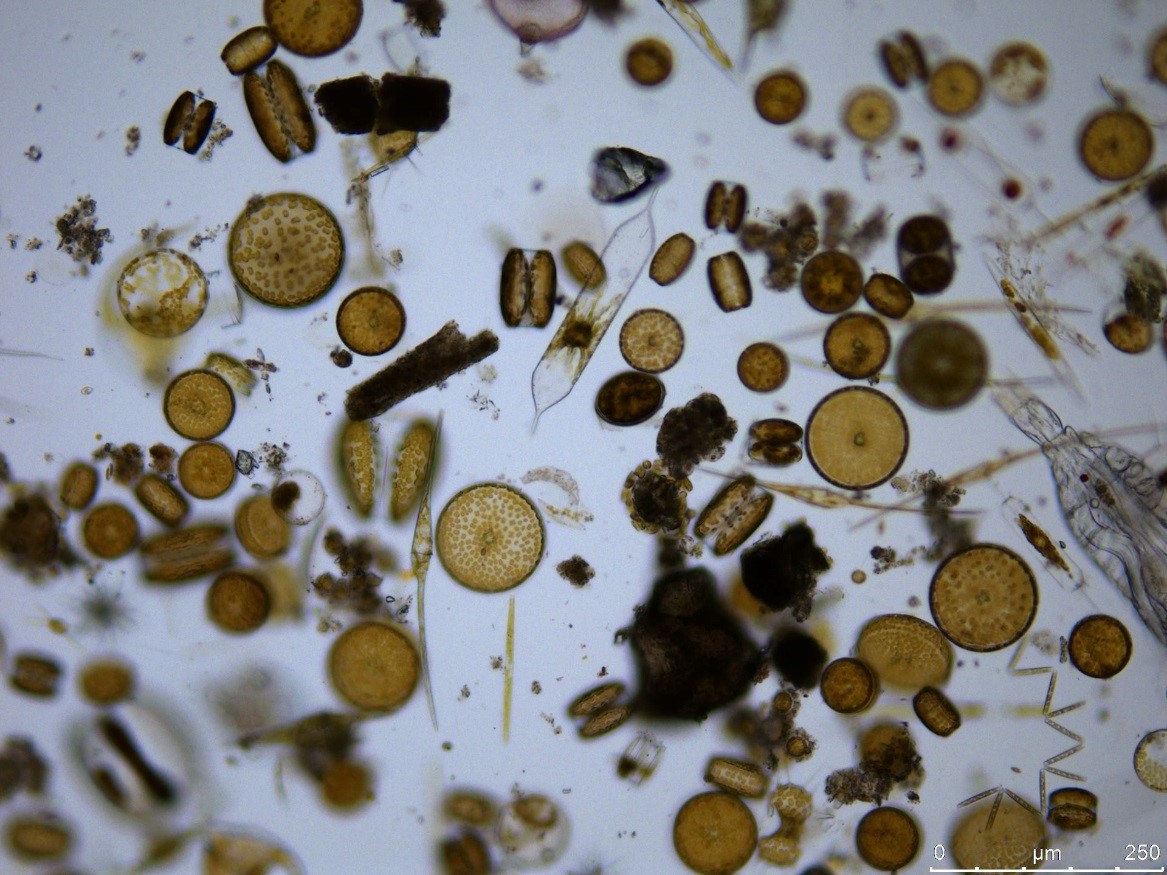

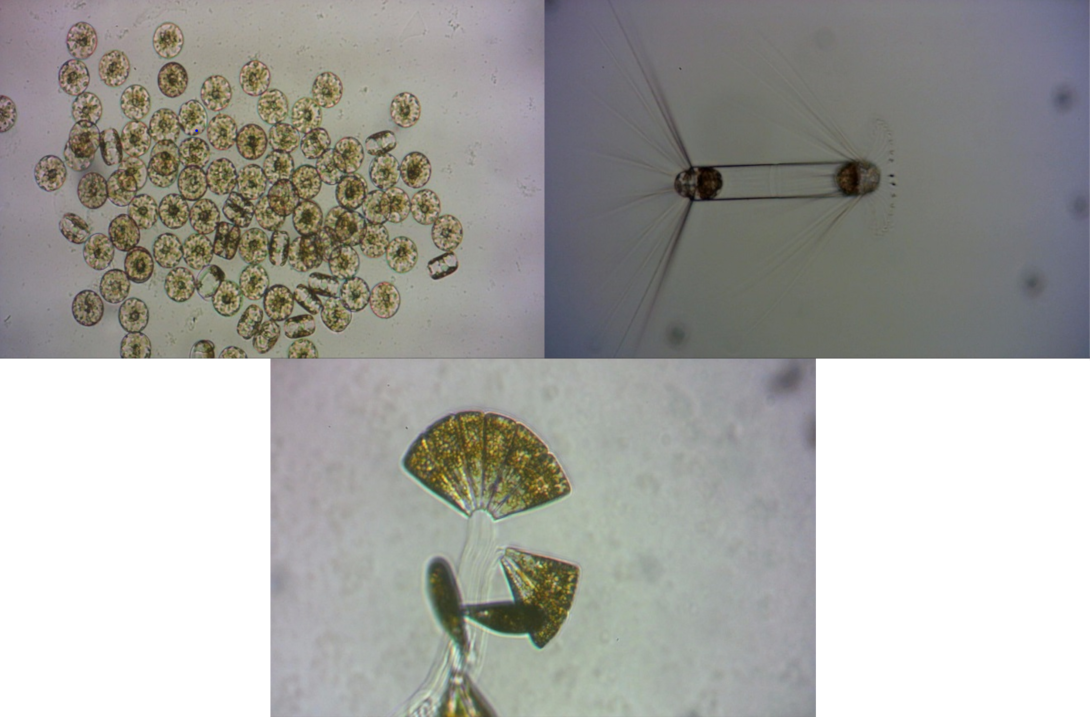

Diatoms are a large, diverse group of microscopic algae which are vitally important for primary production and food webs, diatoms alone are estimated to contribute 20% of global primary production. In the marine realm, diatoms are fundamental to the food chain, providing nourishment to key species such as krill and we all know how important they are. Let’s firstly get one thing straight, though diatoms photosynthesise they are not plants, they are in fact a “Protist”, meaning they are neither a plant nor animal nor fungi. They are unique in forming a “glass” cell wall using silica which is why they are often coined “gems of the sea”.

Diatoms are most dominant in cold regions and waters, this is because these environments have an abundance of nutrients which diatoms require for growth. Antarctica is pretty cold and during the Austral summer there is an abundance of sunlight, a requirement for photosynthesis. The perfect place for diatoms you might say and you would be right, but Antarctica is not just cold, it is freezing. It is one thing to live in the cool waters of temperate environments such as the UK in temperatures around 15°C, but -1.5°C! Just how do diatoms live in such extreme environments? This in part is one of the questions I am asking in my PhD.

En route to Antarctica, our group had seven days in Punta Arenas, and amongst the never ending game of “musical hotels” we did manage to get out and see some of the sights of Chile. The best day was travelling north to the Torres Del Paine national park. For me at least, this was the first time I had ever seen mountains and glaciers up close, the perfect teaser for what was to come.

On the seventh day we were finally given the go ahead for the 4-5 hour flight to Rothera, Antarctica, the British Antarctic Survey’s main base. The weather during the flight was perfect and words cannot describe what it feels like to see Antarctica with your own eyes for the very first time. Upon landing we were given a few days of inductions but once these were out of the way, the sampling commenced.

My first sampling was a momentous occasion, not only because it was the “first” but also because it was an intertidal sample which meant getting highly kitted up for what was simply a little paddle. Employing a bucket attached to a rope originally termed “bucket science” this actually turned out to be one of the best samples of the entire trip.

The majority of sampling however was completed aboard the small RIBs which BAS operate at Rothera. Sampling often took around 3-4 hours in order to collect enough water for various science programmes, therefore, it was wise to bring a few sandwiches and chocolate bars to curb the hunger which will inevitably strike. As diatoms are microscopic, my requirement for water was very small, often only requiring a litre or two. Being out on the water in Antarctica meant there was never a dull moment sampling, with the likes of penguins and seals all making their presence known.

The constant flow of ice drifting gracefully in the water often created a challenging game of dodgems for the boat cox but presented some eye pleasing photos.

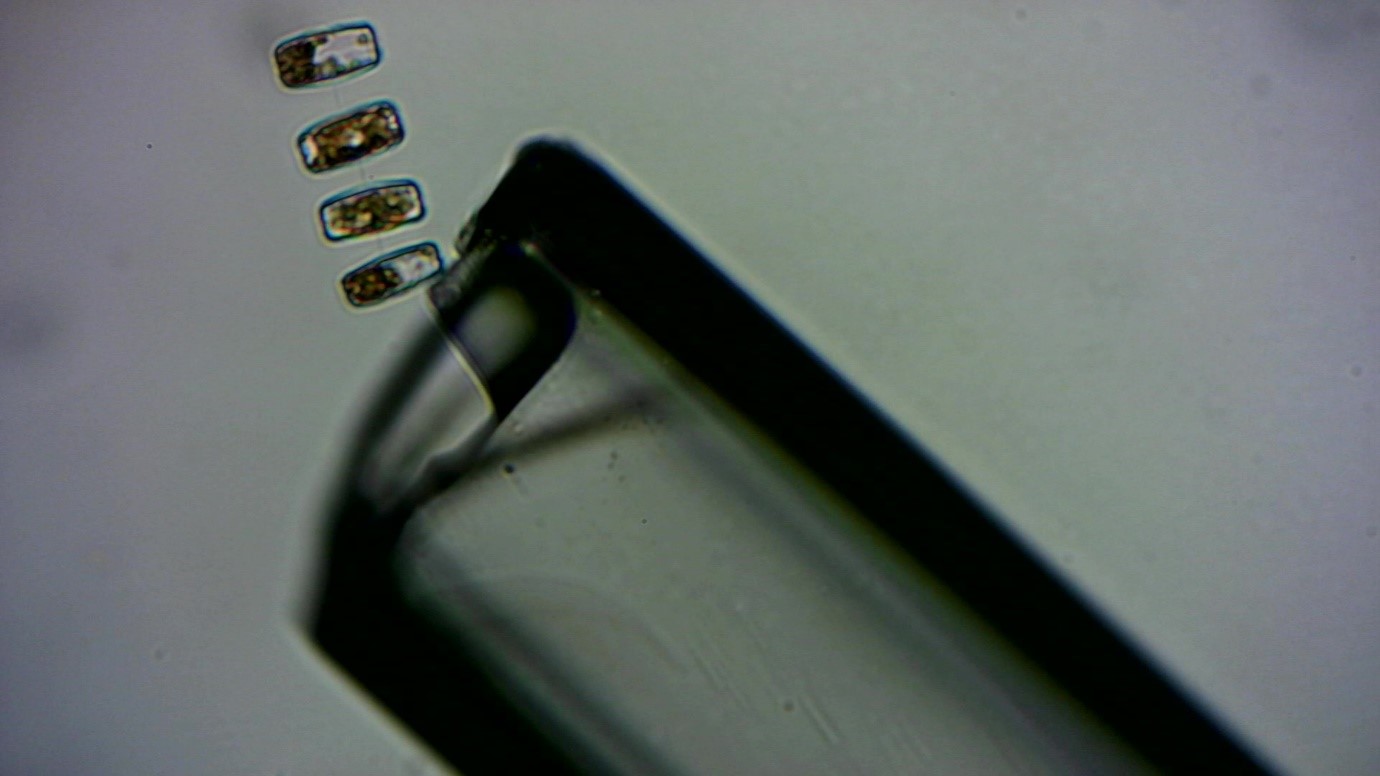

Looking down the microscope revealed the most pristine water samples I have ever seen. The diatom blooms were in full effect for the duration of my fieldwork and this was all you would see. There was no debris in the samples which you often get from samples around the UK and most notably, no plastic. The aim of my fieldwork was to isolate some new cells of four specific diatom species which can then be directly compared to isolates I currently have in the laboratory. Cells were isolated using a very small diameter glass tube called a “glass micro pipette”. The pipette is created at differing diameters depending on the target cell size. Picking cells with a pipette might sound easy, but when you consider the size of the cells <100 microns then it becomes a lot more challenging.

Each day I worked through various water samples isolating cells of target and non-target species. These single cells were then cultured (or not in some cases) to form an established diatom culture. By the end of my time I had manage to establish 24 cultures and had made 100+ isolations which were yet to become established. My cultures are scheduled to return to the UK in the summer, where I will begin including them into experiments to validate previous experiments and make direct comparisons to laboratory isolates.

Due to the nature of where I was conducting field work the wildlife and scenery was a big part of the whole experience. You would often be working in the lab or office and get a shout on the radio of something interesting. For example humpback whales feeding on krill which are ultimately supported by diatoms.

The close working community of base life often meant you could get away from your own work and help out others. One day when I was assisting the dive team, the dive was cancelled due to the presence of Orca, but being on the boat already we got the opportunity to see these majestic animals from the water.

As field work was coming to an end we held an open night in the Bonner lab, this enabled the non-scientist community on base the opportunity to view and discuss the science which we were conducting. There was lots of interest in the diatoms, with many people surprised by just how important these little organisms are. To finish off the evening, we were presented with an amazing sunset sky over the bay.

The two months flew by and all of a sudden it was time for us to depart the base and return to the UK. I prepared all the diatoms for their trip back and said goodbye to all the amazing people I met and worked with on base. Rather fitting, we had another day of beautiful weather for our departure which gave an amazing view of the entire base from the air.

In summary, my field work was a great success in terms of isolating new isolates of polar diatoms and I look forward to working with them soon. The whole experience of working in Antarctica was unforgettable and I would recommend if you ever get the chance to go there to accept it with open arms.

I enjoyed reading this. It teminded me of the summer visitors we had at Deception (1964) and Signy (1965). Prof Tony Fogg from Bangor (?) came to Signy to measure carbon fixation in the lakes and I went bug hunting in bird nests with Prof George Dunnet (Aberdeen) on the cliffs on Deception (1964). Most interesting was probably Simon Rose, PhD student who cultured and isolated bacteria growing in the strange lake in Whalers Bay at Deception. I think it was heated. “Summer Charlies” brought scientific interest and sometimes amusement to base life. Best wishes to Sam Coffin for the rest of your PhD journey.