By Kate Howlett, PhD student at the Museum of Zoology

Wildlife, children and happiness. Not three words you usually think of as being in the same sentence, I’d wager. But this is, broadly speaking, my PhD project in a nutshell. Not your average project funded by an Earth Science DTP, but here I am, two years in, and no one’s called me out yet. I’m going to try to convince you that this is exactly the sort of research DTPs should be funding, and that we need more of it.

I’m researching green space and nature in UK primary school grounds. I’m combining ecological surveys with social science questionnaires and the analysis of children’s drawings to build a broad picture of how these spaces are used, what nature they house and how important they are for kids’ wellbeing, learning and curiosity.

And, no, this isn’t so I can bandy about the buzzword ‘interdisciplinary’ at conferences and networking events. It’s because these human-crafted areas represent a major space in which the next generation interact with the natural world. Omitting any part of this picture whilst potentially the route to a more straightforward PhD thesis, would manufacture an overly simplified story from a complex narrative.

So, why choose to study nature in a man-made environment where we don’t expect to find much of it? Why not spend my fieldwork days walking around a nice nature reserve instead? My project sits within the following context, which is also why I think we need more funded research in this area.

We know there’s a whole host of health and wellbeing benefits which nature provides to people, including improved mood and mental health, reduced rates of cardiovascular disease, and faster recovery from mental and physical stress. We also know that biodiversity is in decline on local, regional, national and global scales, and that urbanisation is on the rise. Increasing proportions of people are living in urban areas and have less contact with nature in their daily lives.

This is particularly true of children, which has led to the coining of the term ‘nature deficit disorder’. As a result, children are not only less able to experience the benefits nature brings, but they are also less aware of and engaged with the wildlife that lives around them. This poses a problem growing in the shadows: how will we recruit the next generation of naturalists and conservationists? These are careers that we and the natural world are in particular need of at the moment.

So, for the last year and half, I’ve been visiting various primary schools across the UK, collecting data on biodiversity, talking with teachers and children, and amassing a large collection of children’s drawings. It turns out this is a topic which almost everyone has a view on. The social data I’ve ended up with are rich and full of interesting themes, which I will eventually get round to sifting through and analysing.

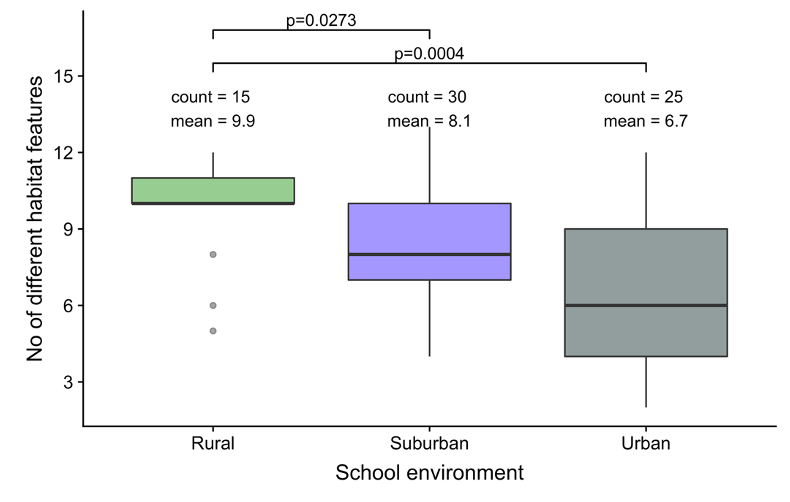

Initial intriguing results suggest that the numbers of tree and bird species are not different between rural and urban schools, despite the difference in greenness of their surrounding environment. What is different, though, is the engagement of rural and urban teachers with the wildlife in their school grounds. Rural schools reported having a greater number of types of wildlife-friendly habitat features in their grounds (Fig. 1); these are things like ponds, bird boxes and insect hotels. So, even if children are not necessarily being exposed to greater biodiversity in rural schools, rural teachers seem to be making more of an active effort to encourage wildlife and engage with the nature around them.

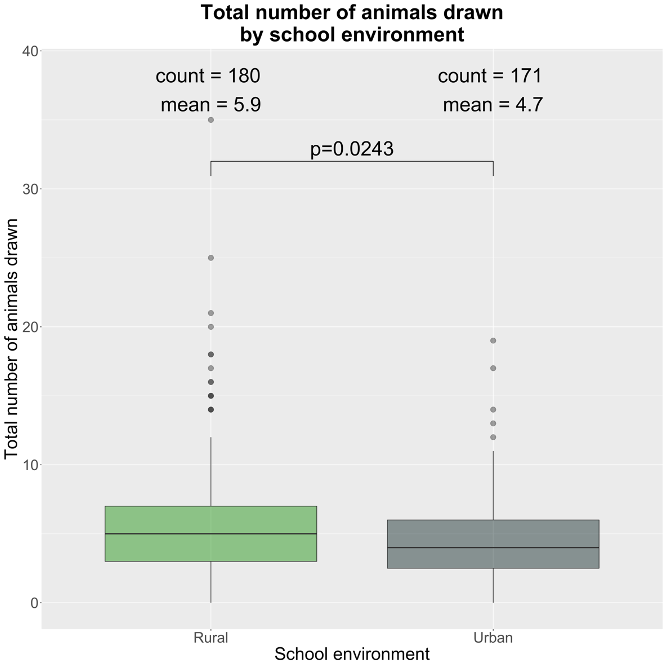

I’ve been seeing the possible effect of this in the children’s drawings I’ve been analysing. I asked children to draw me a picture of their garden or local park, and to label all the animals they think live there. Children at rural schools drew a significantly greater number of different types of animals than children at urban schools (Fig. 2), whilst urban children were more likely to draw a fox than rural children were (Fig. 3).

Figure 2 (left): number of animals drawn and Figure 3 (right): children who drew a fox, by school environment.

This suggests that children’s awareness of the natural world is affected by the nature they encounter around them in their daily lives. And, by extension, this means that there is an opportunity here to increase children’s connection with wildlife by increasing the biodiversity of their school grounds. This would surely be a win-win-win scenario: for nature, for children’s wellbeing, and for the future of conservation.

More hands on deck to try and unpick this complex relationship between children and nature would make all the difference. There are many factors at play here: the influence of the teacher, home environment, local environment, curriculum, and school grounds are surely all influencing how children see the natural world around them. In an increasingly urbanised world, we quickly need to understand how we can reconnect children with nature so we don’t lose a whole generation of naturalists when we need more of them than ever.

2 Replies to “Wildlife, children and happiness: reconnecting the next generation with the natural world”